And ye shall all be freed from slavery,And so ye shall be free in everything;And as the sign that ye are truly free,Ye shall be naked in your rites, both menAnd women also: this shall last untilThe last of your oppressors shall be dead;-From Aradia: Gospel of the Witches, by Charles G. Leland

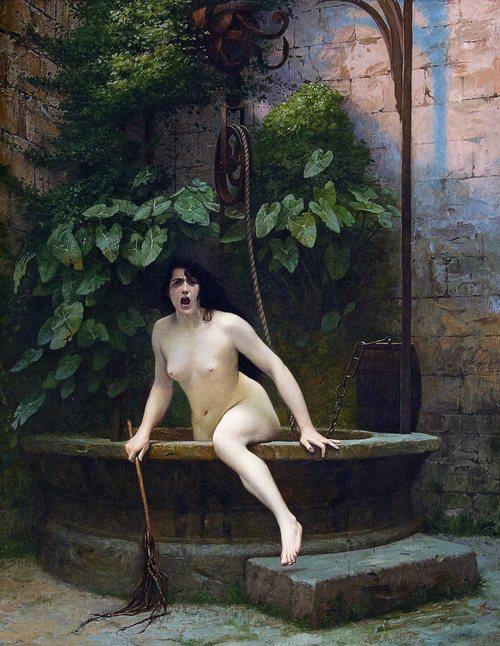

Truth Coming Out of Her Well to Shame Mankind, by Jean-Léon Gérôme 1896 [Public domain] (via Wikimedia Commons)

A lot of modern witchcraft intersects with our bodies. We expect to experience magic as a visceral force, dance ecstatically, use the remnants of bodies–both plant and animal–in our spells, or alternately slather or dab our bodies with magical concoctions to gain a little advantage in a harsh world. In particular, some branches of witchcraft religion, such as British Traditional Wicca, emphasize the importance of bodily acceptance and embrace the human body as a source of power. That power, according to Wiccan progenitor Gerald Gardner, is pulled from the freeing of an “electromagnetic field” by the removal of clothing (although Gardner did allow that he thought “slips or Bikinis could be worn without unduly causing loss of power,” for what that is worth (and please note, I’m not particularly taking Gardner to task here, nor disavowing the traditions he launched, but pointing out that his theories about nudity were influenced largely by his own ideas and experiences).

Recently, people engaged with magic–especially magic and ritual where engagement means contact with other people–have been raising their voices over systematic and ongoing abuse at the hands of elders and community members. Women and young people seem particularly vulnerable as targets of groping, unwanted pressure for sexual initiation, or having bodies simultaneously treated as sacred and sexualized as objects. I am not going to recapitulate the entire discussion of these abuses here, although I will highly recommend spending some time really processing posts like the tough-but-vital ones posted by Sarah Lawless in recent months. Her writing has been excellent and influential, and I have seen countless victims (including many men who experience abuse in neo-Pagan circles) step forward to talk about what has happened to them and insist that it stop (and stop it should!).

That is not my aim today, however, although my topic is tangled into the net of that discussion. I was curious about the role of the witch’s body, specifically the witch’s naked body, as a component of her power or her craft. I knew well the line from Leland’s Aradia quoted above, but I also know that Leland’s sources do not always speak to a broad experience (or even an historically verifiable one, although I value much of his work). Leland’s goddess insists that nudity is an unshackling from the bonds of slavery and a sign of freedom, and Gardner seems to have run with nudity as a liberating experience as well within his own coven. Yet we also see nudity being used to degrade witches, shame them, or force them into the role of living succubus or “red woman” seductress. Where does nudity fit into a New World magical practice? Are there precedents for nude practice, does nudity have any value in practical magic, and does nudity still matter today?

There are essentially two situations in which witches might practice nude in New World witchcraft: alone and in groups. However, even here there are some gray areas, because when a witch is “alone,” they are often not entirely alone. They may be meeting an Otherworldly entity for an initiation rite, for example, and be expected to offer their body up for sexual congress, or even a simple washing ritual. In Appalachian lore, however, the favors were not always sexual, as some initiation rites involved offering a literal piece of one’s body, where “the devil is granted your soul in exchange for some talent, gift, or magical power, it is thought that he then receives some gift of the body in return. This could be a fingernail or even a withered finger.”

Just as often, these initiation rites involve a solitary witch stripping bare, but only as a precursor to other solitary action: cursing or shooting at the moon or (more practically) wading into a river or stream to wash away a previous baptism in some symbolic way. The sexualization of the witch in these encounters is virtually nil, except as perhaps a titillating detail for the listener or a matter of practical necessity for the witch. The act itself is symbolic because the witch is abandoning a previous life–usually a Christian one–and the removal of clothing is much like the washing away of the baptism.

Other parts of the New World also held that witches might strip bare on their own as an abandonment of social order. That was the common perception in Puritan New England, where witches were believed to travel into the woods to meet with “devils” or “Indians” (who were sometimes regarded by European colonists as essentially interchangeable). The idea that witches practiced magic in the buff, however, varied immensely from place to place. Sometimes it is included as a detail in stories of hag-riding, for example, especially in cases where the witch needed to apply a flying ointment of some kind before taking off.

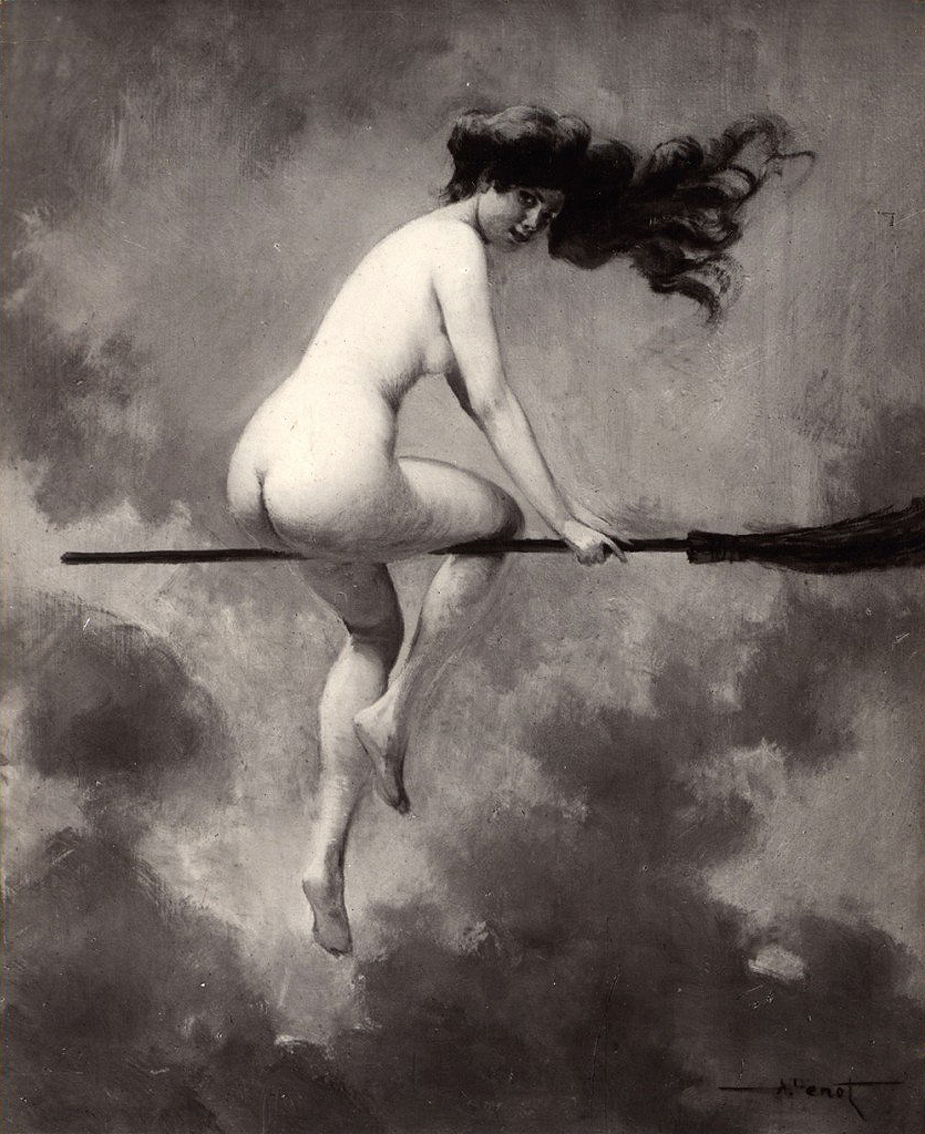

AnonymousUnknown author [Public domain] (via Wikimedia Commons)

Group rituals are often a mixed bag as well, since witches might work in conjunction with another witch at times or meet up with a number of other witches for special events (such as during Walpurgisnacht-type celebrations). In one Ozark story, a would-be witch undergoes her initiation when she “removes every stitch of clothing, which she hangs on an infidel’s [non-believer’s] tombstone.” This rite is witnessed by two other nude initiates, but the sexual congress is relegated solely to the witch and “the Devil,” and not any human initiates. One tale of a pair of sister-witches on Roan Mountain in the Smokies tells of two witches removing their clothing before greasing up and flying up the chimney, for example. Other accounts describe groups of women slipping out of their clothes–or more potently, their skins–before flying off to perform dances. Details of sexual congress appear in European accounts, but are often minimized in North American ones, and frequently even the more diabolical descriptions of group nudity tend not to emphasize sexuality. A number of African tales about witches do indicate that they might have traveled naked to do their work (which was often desecrating graves or hunting children, work that hopefully contemporary witches are not doing). In these cases, however, the nudity was often solitary and never sexual, as the emphasis was on the witch’s wildness and cannibalistic nature rather than her sexual one. I’d also note that in cases where groups of nude witches meet, they are often all one gender (with the exception being the presence of an Otherworldly figure like the Devil), and that when someone intrudes on magical nudity–as happens in the Roan Mountain story–that person is usually punished.

In Zora Neale Hurston’s Mules & Men, she recounts an initiation ceremony experienced at the hands of Louisiana conjure-man Luke Turner (who claimed a lineage with Marie Leveau). In that ritual, Hurston was indeed stripped of her clothing and required to lie on a couch with no food for three days while she waited for a spirit to claim her. Then she was carefully bathed and had a symbol painted upon her, and finally “dressed in new underwear and a white veil…placed over [her] head” after which no one was allowed to speak to her until the ritual was concluded. The nakedness here is again symbolic, but Hurston very much demonstrates that there is no sexual component to it. She is most powerful during the ritual when she is veiled, then eventually has the veil lifted and she is given a “crown of power.”

Some of the most sensational accounts that involve witchcraft-like practices and nudity are those that come out of places like New Orleans in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries or out of Europe in the early Modern period around the time of the Reformation and the Enlightenment. In both cases, one group sought to exoticize another group and ascribing their rituals with depraved sexual fantasies made the stories of witchcraft all the more thrilling (in the same way that many horror films use flesh to both allure and repulse). Simply reading the Malleus Maleficarum opens up a realm of psychosexual fixations that reflect far more on the priest writing the stories than on any reported activities of witches. Scholar Ronald Hutton links some of these concerns to the long entanglement of witches as magic workers to night-stalking demons like succubi, who stole semen from sleeping men and tormented them with sexual dreams. The New Orleans press, in a similar vein, frequently featured stories of “primitive” African American “voodoo dances,” in which scores of naked or nearly-naked black men would dance. The scandal of these stories would escalate–often with particularly dire consequences to the black men–when papers reported white women joining the dances, again often nude. In these sensationalized accounts, the stripping of the body was highly sexualized and often showed the readers of such stories that magic, witchcraft, voodoo, or other forbidden topics would inevitably corrupt those who came too close. Those who know much about Vodoun as a religion, however, know that nudity is not typical to the formal celebrations and rituals to honor the lwa or invite them into a practitioner’s body. Clothing is often very specifically a part of the rites, with specific colors like white being appropriate when performing music or dance or offerings to invite divine interactions.

As often as there are stories of witches removing clothing, there are stories of witches slipping their skins off entirely–something I imagine most witches today won’t do readily–or donning animal skins as a precursor to shapeshifting, as often happened with the skinwalkers of Dine/Navajo tradition. Such practices were also echoed by those who hunted witches, as in Zuni rituals designed to help cleanse a community of witches when witch-hunters wore bear skins to enable them to track witches wearing the skins of creatures like coyotes. It’s worth noting as well that in the Zuni world, many of the accused witches were men, and contact with them required a special water-cleansing ceremony in which those afflicted with witchcraft would be stripped and bathed.

Albert Joseph Penot [Public domain] (via Wikimedia Commons)

So do witches go about in the nude? Absolutely. There’s no reason to think that they don’t. At the same time, do they have to go around in the nude? Absolutely not. Plenty of stories show witches putting on special clothing such as a fur or a veil in order to work witchcraft, and it does not seem to interfere at all with Gardener’s “electromagnetic field” (which, to be fair, even he conceded was not absolutely bound by clothing). Most crucially, except in sensationalized accounts, the nudity involved with witch stories is not particularly sexualized in the New World. There are many tales in which a magic worker might be bare but their nakedness is a symbolic act for them alone, and never an invitation for another person to violate their body. There are always exceptions, of course, but in most cases, we see examples like Hurston’s where a nude witch (or magical practitioner) is treated with extreme reverence and respect, rather than objectified for their body. Only when the nude witch is caught in the gaze of someone outside of her practice (and by someone untrustworthy) does her nakedness become a sexual problem, which seems to say much more about the one doing the gazing (and I, for one, am all for reviving a Euripedes-esque tearing asunder of those who would impose themselves on any gathering of witches in any state of undress).

Naked or not, the witch is powerful. Naked or not, the witch is not to be messed with. Naked or not, the witch does her work, and it is best to let her be.

Thanks for reading!

-Cory

-

Breslaw, Elaine G., ed. Witches of the Atlantic World. NYU Press, 2000.

-

Brown, Karen McCarthy. Mama Lola: A Vodou Priestess in Brooklyn. Univ. of California Press, 2011 ed.

-

Courlander, Harold. A Treasury of Afro-American Folklore. DaCapo Press, 1996.

-

Darling, Andrew. “Mass Inhumation & the Execution of Witches in the American Southwest.” American Anthropologist 100 (3), 1998. 732-52.

-

Deren, Maya. Divine Horsemen: The Living Gods of Haiti. McPherson, 1998 ed.

-

Garcia, Nasario. Brujerias: Stories of Witchcraft and the Supernatural in the American Southwest and Beyond. Texas Tech Univ. Press, 2007.

-

Gates, Jr., Henry Louis, and Maria Tatar. The Annotated African American Folktales. Liveright, 2017.

-

Gardner, Gerald B. Witchcraft Today. Citadel, 2004 ed.

-

Hurston, Zora Neale. Mules & Men. HarperCollins, 2009 ed.

-

Hurston, Zora Neale. Tell My Horse: Voodoo in Haiti and Jamaica. HarperCollins, 2008 ed.

-

Hutton, Ronald. The Witch: A History of Fear from Ancient Times to the Present. Yale Univ. Press, 2017.

-

Leland, Charles. Aradia: Gospel of the Witches. Witches’ Almanac, 2010 ed.

-

Milnes, Gerald C. Signs, Cures, & Witchery. Univ. of Tenn. Press, 2012 ed.

-

Paddon, Peter. Visceral Magic. Pendraig, 2011.

-

Randolph, Vance. Ozark Magic & Folklore. Dover, 1964.

-

Russell, Randy, and Janet Barnett. The Granny Curse and Other Ghosts and Legends from East Tennessee. Blair, 1999.

-

Sprenger, James, and Henry Kramer. Malleus Maleficarum. Public Domain (Sacred-texts.com)

-

Tallant, Robert. Voodoo in New Orleans. Pelican, 1984 ed.