One of the longest-standing charges against witchcraft in the New World (as well as the old) is its inherent alliance with diabolic forces. A person simply could not be a witch without being bound in some way to the Devil or one of his minions, according to popular conceptions which remain strong even today. The notion of witchcraft as a Satanic practice is, of course, inaccurate—many Satanists have nothing to do with witchcraft, and many witches have nothing to do with Satan (that name here being used for the Adversary of the Judeo-Christian God). There are certainly Satanic witches, just as there are Jewish witches or Christian witches.

I prefer to draw a distinction, though, between Satan and the Devil (or devils in general, the capital “D” being used when referring to a singular entity). In most cases, Satan appears in biblical lore as a being concerned with the overall cosmology of heaven and earth, leading wars against God, and presenting deep philosophical and theological complications into the story of Creation. Devils, on the other hand, are creatures interested in particular individuals, usually offering them power or temporal gifts in exchange for a soul, a service, or as a reward for exemplary cleverness. They stem from myriad sources, including the Teutonic Teufel, the trickster spirits of African and Native American mythology, the Norse Loki, and British devil-figures like “Old Nick.” Today, I’ll be looking at the Devil and his role in American witchcraft, particularly his place as an Initiator and a Trickster.

Devil as Initiator

I’ve already somewhat covered this in our post on Initiation, but the Devil (or one of his guises) functions as a primary point of contact for aspiring witches looking for ways to join the Otherworld. While this initiation does often feature some distinctly anti-Christian elements, such as the inverted recitation of the Lord’s Prayer, the Devil’s role in such inductions tends to take on the tenor of a patron or godfather. The Devil “sponsors” the initiating witch, usually offering a physical or magical token in exchange. Some of these gifts include a familiar imp, spirit, or animal – See “Devil beetle bleeding toe” by Davies, or

exceptional magical and/or physical ability (such as the tale of the crossroads by Tommy Johnson, or any of the accounts of gamblers using the crossroads ritual in Harry M. Hyatt). What the witch herself offers the Devil varies a bit. Some examples are:

- The life of someone near to her – “I am told, by women who claim to have experienced both, that the witch’s initiation is a much more moving spiritual crisis than that which the Christians call conversion. The primary reaction is profoundly depressing, however, because it inevitably results in the death of some person near and dear to the Witch” (OM&F, p. 268).

- Her family – As happens, for example, in the Appalachian story of Jonas Dotson, a young man whose granddaddy and daddy were both preachers who decides to become a witch. A very specific ceremony is laid out in the book, involving the use of stolen rams, toad’s blood, a pewter plate, a silver bullet, and an incantation. He undergoes the initiation rite three times before it “takes” and the Devil makes him a witch (or in the context of the story, a conjure man). Basically, he must untie the bonds of family in order to become a magician, and each initiation separates him further and further from those family members. (Davis, p. 22-25)

- A bit of her own flesh or blood – “If, through a pact, the devil is granted your soul in exchange for some talent, gift, or magical power, it is thought that he then receives some gift of the body in return. This could be a fingernail or even a withered finger” (SC&W, p.164).

- Her immortal soul – This is probably the most common story, and is what is frequently meant by “selling yourself” to the Devil. In Vol. 2 of Harry M. Hyatt’s magnum opus on hoodoo folklore, a ritual for meeting the Devil in the form of a tornado at the crossroads ends with “An’ when he [the Devil] gits dere he tells them [the person at the crossroads] exactly whut tuh do, an’ dey’ll dance with him. Dat’s whut chew call sellin’ yo’self to de devil” (Hyatt, p.1346)

- A person’s soul even after death. W.J. Hoffman recounts a Pennsylvania-Dutch legend about a miserly man known as “Old Kent” whose death was presaged by all manner of supernatural occurrences, such as a murder of crows rapping at the windows. After he died, his wife heard such rapping frequently, so often in fact that no guests would stay the night and eventually she had to abandon the house altogether (Hoffman p. 34-5)

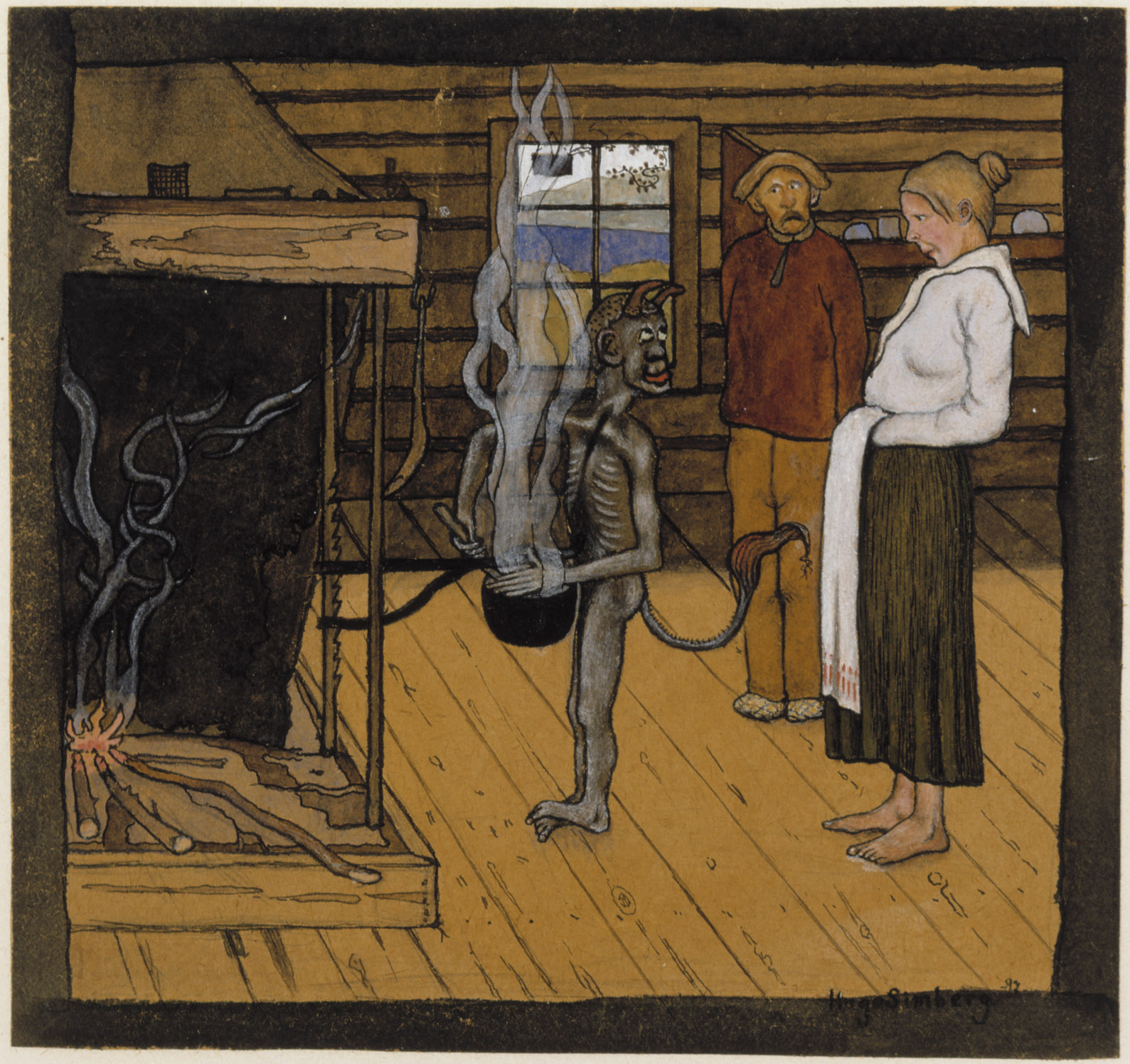

In many of the tales of the Devil as initiator, he also takes the new witch’s name down with a pen in a great black book, signifying the entry of the witch into a long line of witches whose names fill the book’s pages. He is often quite terrifying to those who encounter him. One account of a witch’s initiation witnessed by a couple of country men out in the woods describes him thus:

“Neither me nor Jeff had ever seed the Devil, and we couldn’t believe our eyes, but it must’ve been him. He had horns just above his ears, his feet had hoofs like a deer, he had a long tail like a cow, and fiery eyes that looked like two boiled eggs.” (Davis, p. 17)

Quite frightening, no?

The gifts gained by becoming a witch through compact with the Devil often must be exercised regularly in order to remain potent. Lapsing in witchcraft seems to lead to torment on the witch’s part if the Devil finds that she’s not been keeping up her end of the bargain by using her powers. I would posit that while the folklore here superficially portrays the Devil as a cruel master, he may instead be a necessary goad. After all, what great musician or momentous artist ever became who they are without practice? Again, the Devil may be a stern teacher at times, but one that provides the necessary impetus for improvement in one’s craft.

In all of these particular aspects—mentor/sponsor, gift-giver, book-keeper/librarian, school-master—the Devil rather reminds me of a faculty member at a university, taking a student under his wing, and helping the young witch succeed in her field of calling. But that may just be thoughts spurred on by my gearing up for graduate school again. Because imagining the Devil as some doddering old professor is foolhardy at best. He is, of course, more dangerous than I give him credit for.

Devil as Trickster

Devil as Trickster

Tricksters are common in a number of cultural mythologies, and often have somewhat unsettling or frightening sides. Because of these attributes, the Devil makes a perfect candidate for chief trickster in many folk tales. Just as often as he tricks someone, though, the Devil also gets tricked or outwitted in some way. This flip-side to his role provides a number of amusing tales, but I tend to think there’s a subtle willingness to play the fool on the Devil’s part, making the whole scenario one big trick in the end. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

The lore about trickster Devils is not a New World phenomenon, of course. There are several tales from Europe and Africa which feature a Devil or a diabolical trickster figure of some kind, such as the Grimm’s tale “The Devil’s Sooty Brother” or the Ashanti tales about Anansi the Spider (see Podcast 26). Native Americans, however, also seemed to latch on to the concept of the tricksy Devil, and either came to the campfire with their own Devil tales or allowed a Devil to be integrated into their storytelling at times. A legend recorded by Charles M. Skinner in 1896 discusses a land dispute between the Devil and the Long Island Native tribes which resulted in the creation of a natural landmark (see “The Devil’s Stepping-Stones”).

Skinner also records another wonderful story which has become a tightly integrated piece of Americana. In “The Devil and Tom Walker,” the poor, bedraggled title character meets the Devil in a wood outside of Boston, where they have this exchange:

“Who are you?” he [Tom] asked.

“I go by different names in different places,” replied the dark one. “In some countries I am the black miner; in some the wild huntsman; here I am the black woodman. I am the patron of slave dealers and master of Salem witches.”

“I think you are the devil,” blurted Tom.

“At your service,” replied his majesty.

The Devil coaxes Tom with the promise of treasure, which he at first resists, instead sending his wife to collect it instead. When she disappears, he enters into his Faustian bargain and uses the money to set up a usury business. He attempts at every turn to outwit the Devil, keeping a Bible on him at all times and even burying his horse feet up so that if the world turns upside down on Judgment Day, he’ll have a running start in escaping his fate. Of course, the Devil finally catches Tom and spirits him off to hell, leaving behind only cinders and ashes in place of all his money and possessions.

What interests me about this particular tale is that unlike the European Faust, Tom Walker has no interest in magical gain or supernatural powers—only money. Well, money and getting rid of his wife, that is.

Sometimes the Devil’s trickster competitions are with angels, saints, or even God. In these cases, the Devil almost always loses, but often whatever occurs in the story has some lasting impact on the world. The catfish, according to one Southern folk tale, gets its distinct and ugly appearance from a brush with the Devil. God created the fish, then took the evening off to go up to the “Big House” with his archangels and eat supper. When he came back down to the river, the Devil was sitting there descaling the fish. God demanded he put the catfish back and the devil agreed. The catfish rolled in the mud to make up for its lack of scales but never grew them back again (Leeming, p. 59-60).

Sometimes, of course, people do get the better of the Devil. In a piece of Maryland folklore which parallels the Ashanti story of Anansi and Anene which I told in Podcast 26, a woman (who is never quite identified as a witch, peculiarly enough), enters into a contract with the Devil and outwits him at every turn:

“Not many outwitted the devil, but Molly Horn was one. She and the devil contracted to farm on the Eastern Shore together. They agreed that on the first crop Molly would take what grew in the ground and the devil would take what grew on top. Molly planted white potatoes and the devil came out shortchanged. So for the next crop they decided to do it the other way round, the devil getting what grew in the ground. This time Molly planted peas and beans and once more the devil got nothing. A hot argument ensued on the bank of the North West Fork of the Nanticoke River in Dorchester County. Molly struck the devil a terrific crack and skidded him across the marsh to the edge of the Bay. When he stood up and shook the mud off himself, it formed Devil’s Island, then he dove overboard and made Devil’s Hole.” (Carey, p. 49)

Sometimes, though, people don’t quite get the best of the trickster Devil, and pay a gruesome price. Zora Neale Hurston records the tale of High Walker in her book, Mules & Men, in which the titular Mr. Walker gains necromantic powers from the Devil only to eventually be tricked into losing his head, literally, in a graveyard.

As a final point about the Devil as a trickster, I’d like to look at the Devil’s music. As most probably know, the Devil loves music, especially fiddle music, and can be lured into a fiddle contest on a moment’s notice. If you’ve ever heard the Charlie Daniels Band perform “The Devil went down to Georgia,” you know this story (a Mariachi band once sing this to my wife and me at a large Mexican wedding, which was a pretty phenomenal experience). While it is an entertaining song even on its own, it has precedents in folklore, too:

“It is a well-known old belief that fiddlers make pacts with the devil in order to obtain their talent. Players of old-time fiddle music commonly kept (and still keep) rattlesnake rattles in their fiddles, perhaps unconsciously associating a symbol of the devil with the instrument. The devil appears as a serpent in Genesis, and he is more modernly portrayed playing a fiddle…the instrument has been called the devil’s box, the devil’s riding horse, and similar terms” (Milne, p.153)

Milne also asserts a connection between the rattles placed in the instrument and a similar practice in West Africa, something I’ve not had time to research but which adds an intriguing layer to this particular custom.

Well that’s it for the Devil for today. I have a feeling he’ll be coming back up periodically. When he does, hopefully I’ll be ready for him. Perhaps I should start some fiddle lessons?

Thanks for reading!

-Cory