Really, this entry should be called “pins & needles & spikes & nails & all other kinds of spiky things,” but that would have been an overly long title, so I’m standing by my choice. What I’ll be looking at today are folkloric occurrences of piercing devices as magical tools. This will probably overlap a bit with my entry on iron, but I’ll attempt to cover more new ground than old.

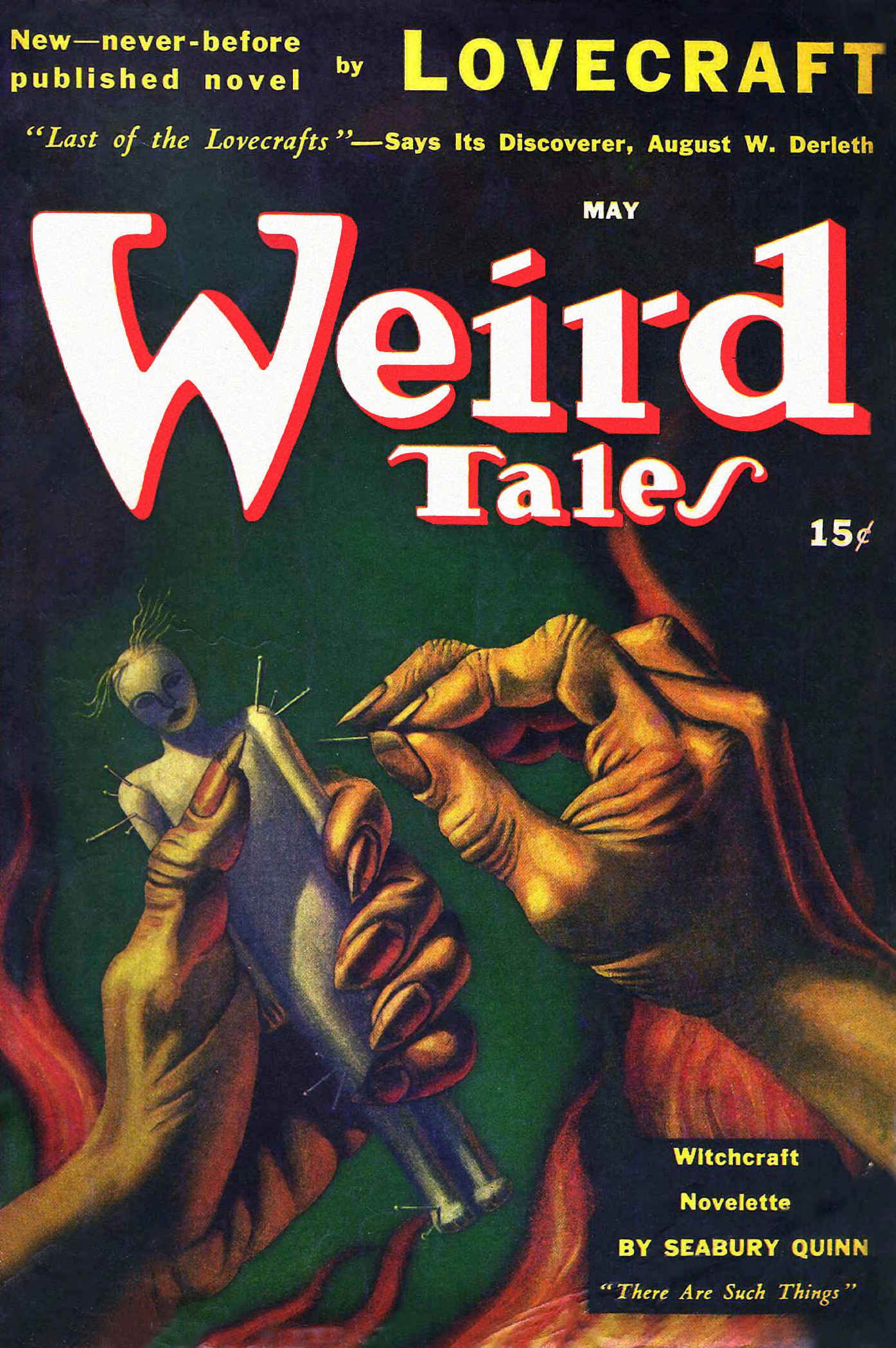

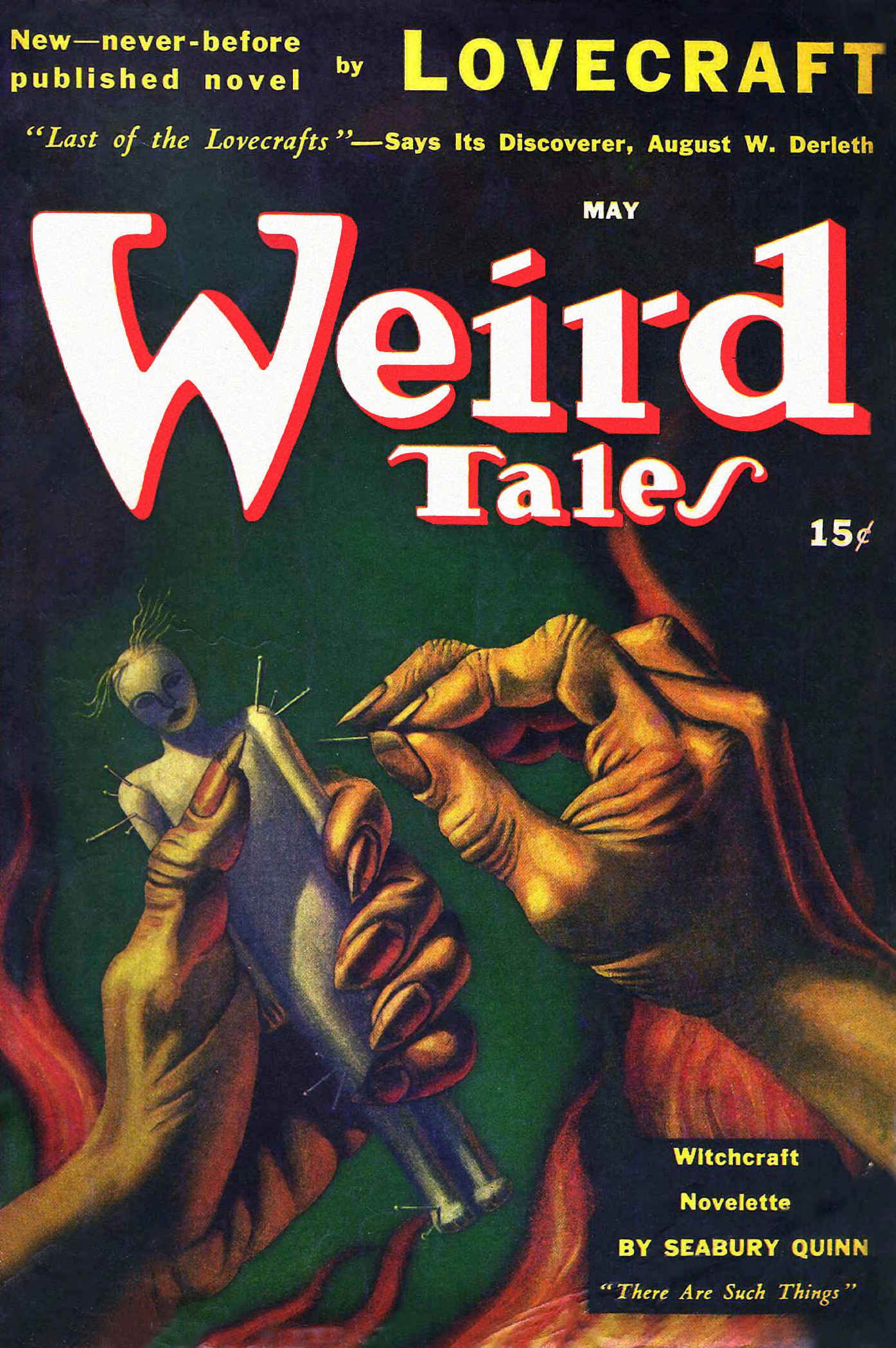

Probably one of the first things to come to mind when looking at sharp-and-pointy things is the popular “voodoo doll,” which is essentially a European-style poppet. These poppets are stuffed with botanicals, curious, dirt, rags, and/or personal items from the intended target and then manipulated to control him or her. Films and television frequently portray only harmful magic being done through these dolls, but a witch or conjurer can also use them to cast love spells, healing spells, or even health and wellness spells. I’ll probably try to do a separate entry on doll magic another time, but it’s worth a mention here, too, I think.

There are some African roots to the voodoo doll phenomenon, including the minkisi minkondi, which were little wooden dolls from Kongo where spirits were thought to live. The doll’s owner would drive a spike into it to “provoke the forces within them” and then the owners would be able to command the spirit to perform certain tasks (Chireau, Black Magic: Religion & the African American Conjuring Tradition). Other cultures have certainly used small effigies of human beings to cause hurt or help, as well. Denise Alvarado has a book which examines these dolls in detail, including a look at corn dollies, fetishes, Greek kolossoi, and other similar magical poppets.

Of course pins and other sharp objects can be used to cause magical harm even without the use of a doll (which makes sense according to the Doctrine of Signatures, which has tremendous influence on much folk magic). Zora Neale Hurston recorded a sinister curse which involved taking nine new pins and nine new needles and boiling them in a nefarious formula called “Damnation Water” in order to cross one’s enemy (Hurston, Hoodoo in America). An old-world carry-over (likely from England, but found in Southern communities where conjure is common) says that burying a pin taken from the clothes of a living person with a dead person will cause the target to die within a year (William G. Black, Folk Medicine).

Probably the most One of the more gruesome application of pin-and-needle magic had little to do with the magical effects of these tools, and all too much to do with their physical dangers: “One instance is given [in an account from 1895] of ‘toad heads, scorpion heads, hair, nine pins and needles baked in a cake and given to a child who became deathly sick’” (“Conjuring and Conjure-Doctors in the Southern United States,” Journal of American Folklore, p. 143). Curing magical maladies often involved finding pins used in spellwork and disposing of them in a ritual way: “He went at once to the hearth, took up a brick, and found sticking in a cloth six pins and needles. He took them up, put salt on them, and threw them in the river. The needles and pins were said to be the cause of so many pains”( “Conjuring…”, JAF, p.145).

A number of ‘Shut-up’ spells—tricks that involve tying the tongue of a gossip or potential witness against you in court—involve taking a slit tongue from an animal like a cow or sheep, packing it with hot peppers, vinegar, and/or salt along with the name paper of the target, and pinning it up with a number of pins and needles (usually nine, but not infrequently more).

Not all piercing spells used metal points. An account of Clara Walker, a former slave from Arkansas, describes her getting help from a rootworker who made a mud effigy of her master and ran a thron through the back of it, causing severe back pain in him (Chireau, Black Magic…)

Pins and needles needn’t be solely used in malicious work, however. A healing spell from England resembles wart charms in Appalachia and some of the rootworker cures from Hyatt’s Folklore of Adams County, requiring pins that have been used to poke or pierce a wart to be sealed in a bottle and buried in a newly-dug grave (Black, Folk Medicine). An account of a mojo bag from the days of slavery tells of “a leather bag containing ‘roots, nuts, pins and some other things,’ which was given to [the slave] by an old man” (Chireau, Black Magic…). The purpose of this bag was to prevent whippings on the plantation where the slave toiled, which could be quite severe.

Pins are also frequently used in witch-bottle spells, which cover a number of different magical traditions, including this version from hoodoo: “Bottles of pungent liquids, pins, and needles were interred by practitioners or strung on trees as a snare for invisible forces” (Chireau, Black Magic…). It would be an egregious error of me not to at least mention coffin nails, too, which are frequently applied in hoodoo and conjure preparations. Usually these are used to inscribe candles with signs, figures, names, etc., but they can also be included in things like war water mixtures or mojo bags to cause hurt and violence. Interestingly, they can be used for protection and health, too. Binding two or four nails into a cross with a little wire or red thread creates a powerful anti-evil charm. Vance Randolph recorded that “nails taken from a gallows [not the same as coffin nails, but rather similar] are supposed to protect a man against venereal disease and death by violence” (OM&F). He also describes these nails being turned into rings by blacksmiths to be worn as protective amulets.

Another hoodoo application involves the use of a series of nails of increasing size, starting with little ‘brad’ nails and getting progressively bigger until you use railroad spikes at the end. The spell is often referred to as “nailing down the house” and requires a practitioner to start by putting the small brads into the corner of each room, and nailing them down, while speaking magic words about protection, prosperity, and stability. Then the conjurer takes bigger nails and nails down the four corners of the house, again praying the magic words. This pattern continues until the conjurer reaches the four corners of the property and nails down iron railroad spikes into the dirt, thus sealing the home from harm and ensuring that the owner will remain in the home and not be evicted. I’ve heard one rootworker say that adding a little urine to each of the nails helps with this work, too, as a way of “marking one’s territory.”

Sewing needles or hairpins can also be used in love spells, as in these from Adams County, Illinois:

- 9641. The significance of a bending needle is a hug for the sewer.

- 9650. If a girl tries on a dress pinned for a fitting, each pin catching in her petticoat or slip will represent a kiss before the day is over.

- 9654. Before going to bed on January 21, a girl may tear off a row of pins (from a new package according to some) , say Let me see my future husband tonight as she pulls out each pin, and then stick them in the sleeve of her nightgown; that night he will be seen in her dream.

- 9655. If a pin found on the floor or street is picked up and stuck in your coat, you will have a date before the week ends.

- 9656. The girl who finds and picks up a pin pointing toward her will see her beau that day.

- 9657. A girl finding and picking up a pin will be dated that night; the man will come from the direction towards which the pin points.

- 9666. For luck in love a girl may secretly put one of her hairpins in her beau’s left hip pocket; this is also supposed to hold him.

- 9669. If while walking along you pick up a large safety pin and name it a man you want to see, he will soon be seen; if a small safety pin and

- name it a girl, she will soon be seen.

The binding power of pins in love spells makes a good bit of sense, and seems deeply entrenched in popular culture; think of high-schoolers being “pinned” (an antiquated notion, I know) or of the description of Cupid shooting arrows or darts to cause romantic feelings in his victim…er..targets. Amorous magic incorporating prickly things is not all lettermen jackets and floating nekkid babies, however. A somewhat heavier love spell from Zora Neale Hurston prevents a lover from straying:

Use six red candles. Stick sixty pins in each candle – thirty on each side. Write the name of the person to be brought back three times on a small square of paper and stick it underneath the candle. Burn one of these prepared candles each night for six nights. Make six slips of paper and write the name of the wanderer once on each slip. Then put a pin in the paper on all four sides of the name. Each morning take the sixty pins left from the burning of the candle. Then smoke the slip of paper with the four pins in it in incense smoke and bury it with the pins under your door step. The piece of paper with the name written on it three times (upon which each candle stands while burning) must be kept each day until the last candle is burned. Then bury it in the same hole with the rest. When you are sticking the pins in the candles, keep repeating:

‘Tumba Walla, Bumba Walla, bring (name of person desired) back to me.’ (Hurston, Hoodoo in America)

There are several agricultural spells which involve driving iron nails or spikes into trees to prevent fruit from dropping off of it (see Randolph, Hyatt, etc.). There’s a lovely bit of distinctly American folklore that says two iron nails driven into your bat will make you a better batter (in the game of baseball, that is).

Finally, I wanted to share an adorably sweet childhood rhyme does not use actual pins, but merely the words as part of a wishing spell performed when two people accidentally speak the same words at the same time. From Hyatt’s Folklore of Adams Co.:

8643. After two persons speak the same thing at the same time, the little finger of the one is held crooked about the little finger of the other and these words spoken alternately:

‘Needles, Pins,

Triplets, Twins,

When a man marries,

His troubles begin,

What goes up the chimney,

Smoke, Knives,

Forks, Longfellow,

Shortfellow.’

They then make a wish and together say Thumbs.

I know there are dozens more applications of pins-and-pokey-bits magic I am not listing here, but hopefully this gives you some idea of what you can do with a simple sewing needle or a couple of iron nails. Magical tools are everywhere, if you know what you’re looking for, and how to use them. But for now, I’ve waxed on long enough about this topic, so let’s stick a pin in it and call it done.

Thanks for reading!

-Cory

![By Julius Nisle (died 1850) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://i0.wp.com/upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/7/75/Teufelspakt_Faust-Mephisto%2C_Julius_Nisle.jpg)