Coins as magical objects in folklore are ubiquitous, appearing in multiple forms and for multiple purposes. Just think of the common-place act of flipping a coin, which is essentially allowing chance (or Fate) to decide the outcome to a given situation. People frequently carry lucky pennies or coins from their birth year to provide a little extra good fortune in their lives. Many people collect coins from foreign lands because of their exotic and seemingly mystical nature (the I Ching coins of Asia are a good example). Today I thought I’d take a very brief look at magical coins in American folklore. I’ll primarily focus on two key denominations, the dime and the penny, though these will be entry points for examining other aspects of coin magic, too.

Silver Dimes

The most famous of these magical coins is the “Mercury dime.” While actually inscribed with a picture of embodied Liberty, the idea of Mercury has long been attached to this coin. Cat Yronwode says “this makes sense, because Mercury was the Roman god who ruled crossroads, games of chance, and sleight of hand tricks” and associates him as well with Papa Legba (Hoodoo Herb & Root Magic). Coins from a leap year between 1916 and 1946 are especially lucky. Yronwode lists it as among one of the most potent hoodoo tokens, and tells of its uses in aiding gamblers, helping one get a job, or fighting off evil. In this last capacity, the easiest method is to simply punch a small hole in the dime and tie it with a red thread around one’s ankle. The dime will turn black in the case of magical attack, simultaneously deflecting it and warning of its presence. In her book Black Magic: Religion & the African-American Conjuring Tradition, Yvonne P. Chireau mentions this use of the dime, along with several other forms of dime divination, including boiling the dime with items suspected to be tricks to see if they contained malefic magic. According to Chireau, a person suspected of being jinxed could put a dime under his or her tongue to detect the presence of evil work, too.

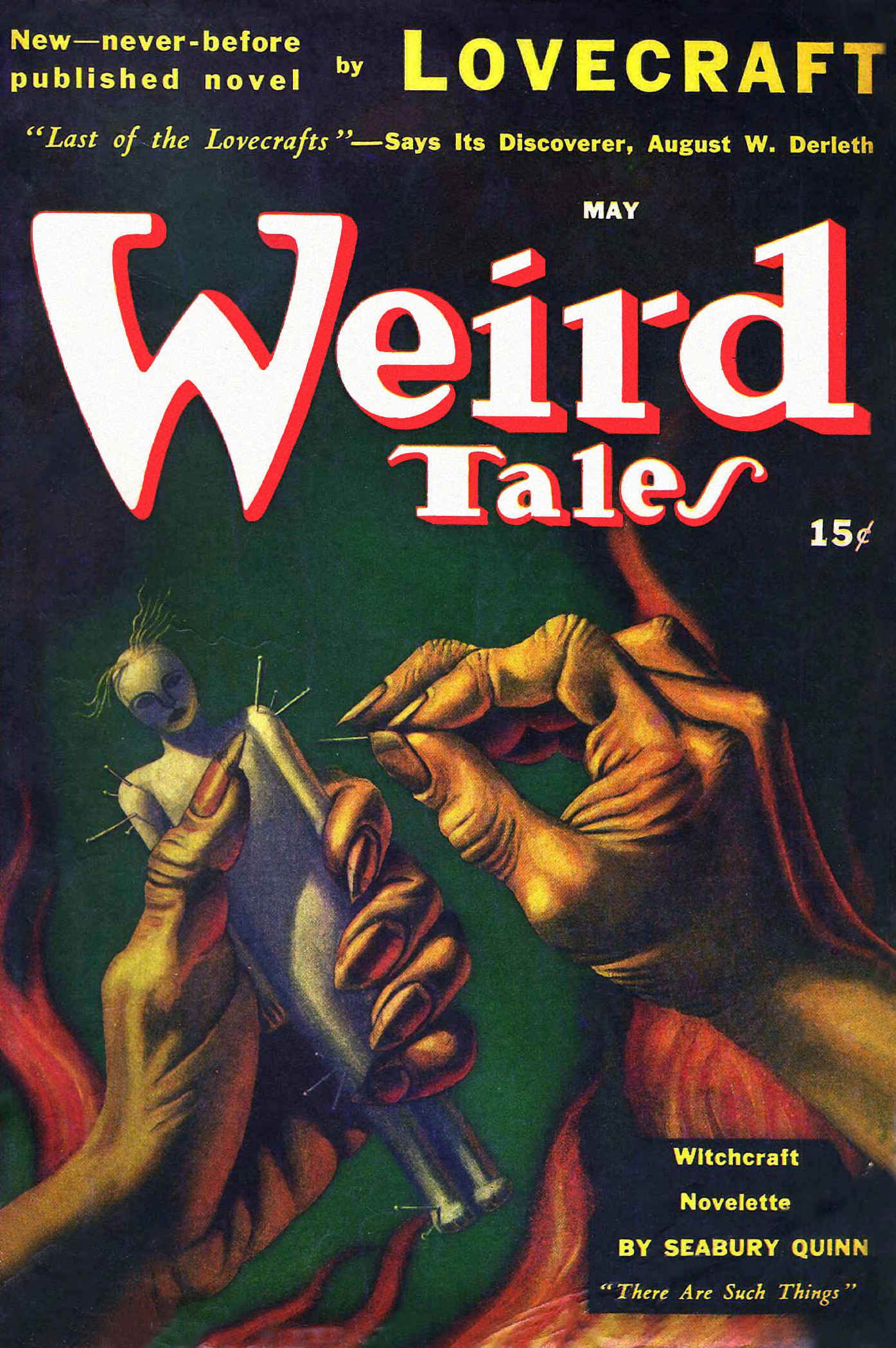

Silver coins in general are thought to be useful in counteracting witchcraft. From A Collection of Folklore by Undergraduate Students of East Tennessee State University: “The method to ward off witches was to carry a piece of silver money or to wear a piece of silver on a string around the neck. The coin most commonly used was a dime” (64). In a story called “A Doll and a Bag of Money,” from The Silver Bullet by Hubert J. Davis, a woman named Aunt Nan Miller tells a tale in which a bag of silver and gold coins magically comes to her. One of those silver coins later saves her family when they melt it down and use it to shoot a doll of a witch who has been plaguing them.

A silver coin placed under a butter churn could help counteract minor witchcraft and get butter to come unless the spell was severe. In that case the milk was scalded in fire or whipped with switches to torment the witch spelling the churn. An informant cited in Gerald C. Milne’s Signs, Cures, & Witchery seemed to think that the coin should be heated to a high temperature and added to the churn, and that the presence of the words “In God We Trust” on the coin had something to do with its power, though that would only date the practice to the 1860’s, when that motto first appeared on U.S. coinage.

The presence of silver in the coin seems to be its key to potency, as modern dimes (those produced after 1963 when the U.S. Mint drastically reduced the silver content of the coins) are not frequently used to the same effect.

Lucky Pennies

The concept of the lucky penny is widespread in America. I even have a lucky penny keychain given to me by my younger brother from a trip he made to Las Vegas. They apparently sell them in the casino lobby. Patrick Gainer describes a lucky penny worn as a podiatric accessory: “If you wear a penny in your shoe, it will bring good luck” (Witches, Ghosts, & Signs 123). This is quite likely the origin of penny loafers. And of course, there’s always the nursery rhyme/thinly-veiled-bit-of-witchery:

See a penny, pick it up,

All the day you’ll have good luck.

See a penny, let it lay,

Bad luck follows you all day (this is my own recollection of the rhyme, and there are many variants of it)

The “Indian Head” cent, a copper coin produced between 1859 and 1909 in the United States, is thought to be an especially useful incarnation of the lucky penny, able to perform almost conscious acts of magic on their own. Yronwode describes them as ‘Indian Scouts’ which can be used to keep the law away from your property (especially if you are engaged in illicit activity). The easiest way is to simply nail them around doors or windows. One method described by Yronwode has the penny being placed between two nails which are then flattened into an ‘X’ shape over it to cross out the law’s power to find the place.

Yronwode’s Lucky W Archive has a very in-depth study of lucky coins, including the penny, which I will avoid quoting as simply visiting her site will provide far more insight than any summation I can give here. We also discussed lucky pennies and coins a bit in Podcast 13 – Lucky Charms, so give that a listen, too.

Magical coins aren’t solely limited to these denominations, of course. The more general idea of a magical coin appears in a variety of literature and folklore. In Melville’s Moby Dick, for example, Captain Ahab nails a coin to the mast of the ship as a temptation to the men to seduce them into his quest for the white whale. This is related to maritime folklore in which coins would be nailed to the mast for good winds and luck (American Folklore 962). From Hubert Davis comes the story of Pat who tricks the Devil into becoming a coin to pay a bartab and then puts him in an enchanted purse (this is a variation on a Jack tale in which Jack outwits the Devil—in the Jack variants he frequently uses a Bible or something marked with a cross to contain the Devil). Pat refuses to free him until the Devil promises never to take Pat to hell. This becomes the story of the Jack-o-Lantern in some versions, of course (Davis 163-166).

One of the most interesting applications of magical coins I’ve found comes out of Appalachia (and has precedents going back further) and has to do with curing warts. People with a certain gift could rub a person’s wart with a coin, usually a penny, and then tell him or her to spend the penny and thus give away the wart. My brother-in-law’s grandfather reputedly had this ability, being the seventh son of a seventh son. He had an upstanding reputation as a good Christian man, but he was able to do both wart charming and well dowsing, showing (to me at least) that magic can easily transcend religious barriers. This sort of curing is also described in Milne’s book, along with other wart cures favored by Appalachian healers (Milne 159). Coins can also be used to pay the dead who work with you; my own teacher taught me that graveyard dirt should be bought with three pennies and a shot of whiskey or rum. And a court spell from Voodoo & Hoodoo by Jim Haskins also mentions the coin as a useful component of love spells, particularly ones which require someone to stick close b you physically (Haskins 185).

There are many other bits of lore regarding coins and magic, of course, but sadly I must draw this entry to a close somewhere, and for now I think it’s best to cash out here. If you have good magical uses of coins, please feel free to share them!

Thanks for reading,

-Cory